As a teenager, channel 31 on our television was strictly forbidden in our home. Lucky for me, this was decades before the invention of parental controls. It was easy for me and my siblings to sneak downstairs to watch what we believed was the greatest development in the history of television – MTV.

Before the launch of MTV (Music Television) in 1981 the only way we really enjoyed our music was by listening to it on the radio. It was a strictly mono-sensory experience. MTV revolutionized how we enjoyed our music. Although it is different today, MTV was originally designed to simply play music videos 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. My siblings and I would stand in front of our T.V. and become fully immersed in this multi-sensory experience.

We watched Madonna with wide eyes. We listened to Whitney Houston and even tried to sing along on those high notes. We were mesmerized by how Michael Jackson could move his body and tried to mimic those moves. Each of these elements enhanced and enriched our musical experience.

A similar revolution is needed in classrooms across the world.

The Research

The principles used to design MTV apply to any learning situation. The more sensory inputs (seeing, hearing, doing, etc.) we can activate in our students’ brains, the more enhanced and enriched their learning will be. The memories will be stronger and recall will be easier (Schneider et al., 2018).

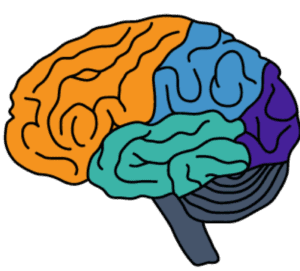

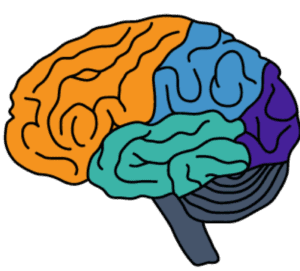

In a similar way that MTV created a multisensory television experience, the letters MAV can be used to describe how the brain creates its own multisensory educational experience. The M represents the motor cortex, the A the auditory cortex, and the V the visual cortex. These are the three main sensory channels into the brain that we have available to us as teachers to help construct new learning with our students.

Motor Cortex (M)

The motor cortex runs across the top of the brain from ear to ear, almost like a headset. Its main function is to process and store memories relating to movement (Vitrac et al., 2017). Your motor cortex is involved in the storage of: the Electric Slide dance moves, the itchy wool sweater your grandma gave you, and the pencil motions you make to write your name.

Auditory Cortex (A)

The auditory cortex is located in both hemispheres of the brain (left and right) and is directly behind the ears. This is a convenient location for the auditory cortex to perform its function of processing and storing memories associated with sounds – words, volume, tone, music, etc. (Zatorre et al., 2002). Your auditory cortex is involved in the storage of: the sound of your child’s laugh, the melody of the Star Wars theme song, and the sequence of your abc’s, including the tune you used to learn them.

Visual Cortex (V)

The visual cortex is located in the back of the brain. Its primary function is to process and store memories related to sight – color, shape, size, etc. (Murray et al., 2016). Your visual cortex is involved in the storage of: the face of your 3rd grade teacher, the color of your first car, the shape of a regular pentagon.

How We Remember

With a basic knowledge of these three sensory cortices we can begin to understand how memories are recreated. First, it is important to recognize that memories are not stored in one specific location in the brain. Pieces of our memories are scattered throughout the brain in the appropriate sensory cortices and a few other locations. When we are prompted to recall a memory, all the pieces converge to one central location in our frontal lobe, located directly behind the forehead. This is the home of working memory – the memory processing system that allows us to hold memory long enough to organize and use it (Simons, et al., 2003).

In everyday life it works like this:

A friend asks about your vacation last summer. As you pause for a moment to think, your working memory is diligently searching for all the pieces of memory from that special vacation and bringing them all together.

Your working memory accesses memories in your motor cortex about the activities you were physically engaged in during that vacation – hiking, laying by the pool, driving in circles when you were lost, etc.

Simultaneously, your auditory cortex is contributing its own unique memories – the sounds of the local language or accent, a memorable conversation you had with a local, the sounds of the waves crashing on the beach, etc.

Your visual cortex is also engaged in recalling what it has stored – the layout and décor of your hotel room, the sites you visited, the color of the hat you bought as a souvenir, etc.

All of these pieces converge together in your working memory as you begin to tell your friend about your wonderful vacation.

(Yes, there are other senses involved too. Our focus here is mainly on the three dominant learning channels we tune into in a school setting – M, A, and V.)

This process only works if various forms of sensory information was input in relation the experience.

If Cortices Could Talk

A similar process plays out daily for students in their classroom. Unfortunately, it isn’t always as smooth.

Imagine a student is in an exam. She is presented with a question about voting rights in the 1960’s. Her working memory goes to work to collect everything it can find throughout her brain relating to this topic. How she learned about this will determine how much information she is able to gather. If sensory cortices could talk, perhaps they might say the following when approached by working memory:

Auditory Cortex: “Hmmmm … voting rights in the 1960’s? Yeah, I think I remember the teacher talking about that. In fact, I remember a lot of talking. Oh yeah – there was that one story he told about … Here are a few things I think I remember the teacher saying …”

Visual Cortex: “Voting rights in the 1960’s? Uhhhh … I think I remember the teacher wrote something on the board. I don’t think I have any notes on this, though. And I don’t remember watching any video clips or looking at any pictures or charts. Sorry, I don’t have much to contribute.”

Motor Cortex: “Ha! This is a joke, right? You really think I, the motor cortex, was involved? Not a chance. I just sat there in my chair all day. I have nothing to contribute. Good luck!”

Perhaps it is a good thing that our student’s sensory cortices can’t talk! Or maybe it would be helpful to hear their neurological cries of “Feed me! Feed me!” There is no way for our brain to recall information that was never put in there. If a student’s visual cortex was not involved in the learning, it will have nothing to contribute at the time for recall.

A similar experience can happen any time a student is asked a question, working on an assignment, or any activity where they must draw upon something they were taught.

Using just one sensory cortex is a less enriching experience than it could be if there were more senses involved. In addition, this approach leaves a sole cortex responsible for recall. That is a heavy weight of responsibility to place on one cortex.

The main takeaway is this: students learn and retain information better through a multisensory learning experience.

Practical Application

To maximize student engagement, learning, and retention follow the MTV model.

Aim to activate the three main channels for learning – motor cortex, auditory cortex and visual cortex in every lesson. You might be thinking, “Oh great! That is three times the work!” Not in the way you might be thinking. We often forget the simple strategies that activate these various cortices. Multisensory instruction does not require hours of preparation with your workstation covered with colored paper and scraps of lamination lying around. Accomplishing this goal can be simple. Here are a few classic hits to remember along with some new releases to add to your mixed tape of multisensory instruction hits.

Motor Cortex

Remember the Classics:

- Note-taking: the simple act of writing things down is a powerful strategy to engage their motor cortex.

- Manipulatives: let students engage in physical manipulatives to help model their mathematical thinking at ALL ages and levels of math.

- Gesture the learning: put motions to new vocabulary terms (ie. parallel/perpendicular lines), processes, etc.

New Release:

- Heads Up: Tape a 3×5 card on each student’s forehead as they enter the room. On the 3×5 card have a term written that relates to your unit of study. Students walk around the room asking each other Y/N questions to gain clues about their term until they guess correctly.

- Multiple choice walls: Tape 4 different solutions/concepts to the four walls of your classroom. For example, the four walls could say quadratic function, linear equation, cubic function, and “other”. Students are given a stack of cards with different functions on them. Students work in groups to categorize and tape the card to match the four categories.

Auditory Cortex

Remember the Classics:

- Pause: slow your pace of speech when saying something very important

- Callbacks: invite students to repeat key words, ideas, or instructions back to you, or to a neighbor

- Think-Pair-Share: Allow students time to talk about what they learned that day with a classmate

New Release:

- Amnesia: After learning new material, students partner up and imagine the other is experiencing temporary amnesia and forgot all that was learned. The student then reteaches their partner everything they remember as if their partner is hearing it for the first time.

- Musical Chats: Chairs are set up in partnerships – two chairs facing each other – scattered throughout the room. Have one less chair than the number of students. When the music comes on, students walk/dance around the room. When the music stops, they quickly find the closest empty chair to sit in. With their partner, they engage in a conversation, partner reading, problem completion of your choice. The student who wasn’t able to find a seat gets to be partners with the teacher. It can be a great way to have one-on-one time with a student and check-in on their learning.

Visual Cortex

Remember the Classics:

- Picture it: Invite students to pause and picture what they just learned

- Anchor charts: Post anchor charts and other visual aids. For added effect, have students create the anchor charts.

- Mind maps: Incorporate mind maps and other graphic organizers

New Release:

- TikTok: Design a project where students work together to create a TikTok video that gives a visual representation of the content they are learning. Give specific parameters to keep the focus on learning. Host a showing party for all groups to share, and perhaps a contest where other classes can vote for the best TikTok in different categories.

- Meme: Tap into the meme culture and guide students to create a meme for your current content. To get their creative ideas flowing, consider sharing a few of Howie Hua’s famous math memes.

The principles that made MTV a joyful, enriching experience can easily be replicated in our math classrooms. Pick a strategy or two from above to try this week and watch your students’ learning come alive.

Citations:

Murray, M. M., Thelen, A., Thut, G., Romei, V., Martuzzi, R., & Matusz, P. J. (2016). The multisensory function of the human primary visual cortex. Neuropsychologia, 83, 161-169.

Schneider, S., Beege, M., Nebel, S., & Rey, G. D. (2018). A meta-analysis of how signaling affects learning with media. Educational Research Review, 23, 1-24.

Simons, J. S., & Spiers, H. J. (2003). Prefrontal and medial temporal lobe interactions in long-term memory. Nature reviews neuroscience, 4(8), 637-648.

Vitrac, C., & Benoit-Marand, M. (2017). Monoaminergic modulation of motor cortex function. Frontiers in neural circuits, 11, 72.

Zatorre, R. J., Belin, P., & Penhune, V. B. (2002). Structure and function of auditory cortex: music and speech. Trends in cognitive sciences, 6(1), 37-46.